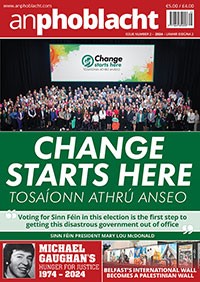

10 June 2024

A prisoner’s Christmas

• Martina Anderson and Ella O’Dwyer

In 2007, for a Christmas edition An Phoblacht sat down with Ella O’Dwyer and Martina Anderson to capture their prison Christmas experiences. It is a great insight into the comradery among prisoners at the time, and crucially into the wit and humour of Ella, who will be greatly missed by all who knew her.

Vintage stuff from English jails - Ella O’Dwyer and Martina Anderson recall Christmas and other ‘happy’ times as republican POWs

First published: 20 December 2007

ELLA O’DWYER is from County Tipperary. MARTINA ANDERSON is from the Bogside in Derry. Both were arrested in Glasgow in June 1985 with Gerry ‘Blute’ McDonnell, Peter Sherry and Pat Magee, ‘The Brighton Bomber’. Ella was 26 years old. Martina was 23.

The following year, on 11 June 1986, all five were given life sentences at the Old Bailey in London for planning IRA attacks. Ella and Martina served their time in Brixton Prison and Durham Prison before being transferred to Maghaberry Prison, near Derry, in 1994. After serving 13 years in jail, they were both released on 10 November 1998 under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement.

Ella is now a staff writer with An Phoblacht and her book, 'The Rising of the Moon: The Language of Power' (Pluto Press, London), on literature, language and Irish history, is based on the MA and PhD she completed in jail.

Martina got a first class honours degree in social science while in prison. She was elected as a Sinn Féin Assembly member for Foyle earlier this year and is a member of the Policing Board. She is the party’s spokesperson on Equality.

Ella’s account

BEARING in mind that it’s 22 years since Gerry McDonnell, Pat Magee, Peter Sherry, Martina Anderson and myself were arrested, some of the finer details, especially of Christmases, are lost on me, and it wasn’t from hooch – at least not until the Christmas of 1994 when we were transferred back to Ireland where our comrades in Maghaberry Prison had prepared a party of note.

We were lifted in Glasgow in June 1985 and transferred to London.

Our first night in Brixton Prison was awesome. I had a real bed and a room with a view. Just as I was bedding down for the night I heard a voice from the cell below asking me if I wanted a fag. He advised me to unravel threads from the blanket, knot them together to make ‘a line’. I did just that and dropped the line down to the window below and, a few seconds later, I was smoking blissfully to the tune of, “Every little thing is gonna be alright,” rendered by the Good Samaritan below.

As far as the prison regime was concerned, Martina and I were persona non grata. When an alleged spy from East Germany called Sonia arrived at Brixton she was told as much. If she kept away from us she’d be ‘all-rightish’, but if she befriended us she’d get the same treatment as we were getting – up to five strip-searches, around six body-searches a day, relentless cell-searches and usually 23 hours’ lock-up a day. Sonia befriended us nevertheless, right to the end. She was with us for our first Christmas in Brixton Prison and it snowed that morning. We got out to the yard and, like mad children, drew Christmas messages on the snow to people who’d never get to see them. We exchanged presents and read the greetings in An Phoblacht – Ann and Rab of the POW Department, our families and God knows how many others. We even got our faces on the front page of the paper one Christmas. What a blast!

But Brixton wasn’t exactly a pantomime. As one member of the Board of Visitors said: “The only thing you are entitled to here is to be fed, wear clothes and get an hour out of the cell per day.” And that basically was our gettings. But my mother used to always tell me growing up that a bit of hardship toughens you for things to come. She was always a bit of a wizard that woman and, sure enough, Brixton was the training ground for even bigger things – H-Wing, Durham.

In our naiveté we’d been kind of looking forward to the move to H-Wing after the ongoing conflict with the screws in Brixton and the sometimes very abusive manner of the male prisoners there. My first sighting of H-Wing gave me the distinct impression of a big dirty chimney but I still didn’t know how the hell Santa Claus was ever going to get down it.

The first person I remember seeing as we went onto the wing was an old lady of about 70. She was remarkable for the fact that she’d push a sweeping brush a few feet, stop suddenly and say, “Half-past four,” in a broad Cockney accent then continue to push forward another bit.

The word ‘smoke’ must have been written on my forehead even then because she made a beeline for me to ask for a light. No problem, I thought, until a screw came up and told me she was an arsonist and not to be given a light under any circumstances!

The ‘half-past four’ thing emerged from the fact that she was meant to have been hung a number of years previously at half-past four and got reprieved to Durham. Some reprieve.

Soon we had two Martinas with the arrival of Dubliner Martina Shanahan, one of the Winchester Three, in 1987.

We were thrilled at the arrival of one of our own but a bit despairing too in the knowledge of what lay ahead of her. We three became close – she was our baby though she had more sense than the two of us put together.

Martina Shanahan was only in the place a day or two when Anderson and myself were for the block for something we’d done before her arrival. Shanahan was inconsolable: her two closest friends in the place were being locked up and she wasn’t. We’d a bit of a job convincing her of the importance of the responsibility we were now placing on her young shoulders. She’d have to be out on the wing to write out letters about our ‘dreadful’ plight and hold the fort ‘till our ‘release’ while we suffered great toils and torments! We could hardly hold the laughter in. Pretty soon, she was for the block too.

Then the Winchester Three won their appeal in 1990 and we were wracked by conflicting emotions: joy at seeing her released and yet the sadness of letting her go.

There were times throughout the Durham period when we’d have run-ins with the other prisoners but we made it clear that neither the system nor the prisoners could come between us - and that clarity was sometimes delivered in less than gentle ways. They say that if you’ve a reputation of getting up early you can get up at mid-day.

But this again is a Christmas tale and when we were transferred to Maghaberry we had a Christmas never to be forgotten.

We were met on the first visit with the delighted faces of our families – the people who had gone through so much hardship on our behalf for all those years.

While walking around that exercise in Durham under the dingey, grey chimney of H-Wing I’d sworn that if I ever got back under an Irish sky I’d kiss the ground on the first Christmas there. If the Pope was good enough to kiss it, so was I. And that’s how I’d begun Christmas morning, 1994. It was one hell of a Christmas.

I remember saying to the O/C, Mary McArdle, that people outside would have paid to come into a party like this. “I doubt it,” said Mary. Marie Wright (RIP) complained that the hooch was below par and nothing like the usual quality. Martina and I disagreed. It was like fine wine. 1994: a good year — vintage stuff.

Martina’s account

BY THE TIME we arrived at Brixton, after ten days’ interrogation, I was shattered tired and couldn’t care less about my new surroundings. I needed sleep without expecting the door to open for more questioning. So while Ella was on a full-scale op’ trying to get fags through her window, I was out for the count.

We spent most of the next 13 months with no clothes on, with all the strip-searches we were getting. By way of protest we were for refusing to put the clothes back on after the next strip-search and just wear dressing gowns but for the wise intervention of Mitchel McLaughlin. More often than once, Mitchel helped us see the light during the many visits he made to us in jail.

Another time we refused to put our cells back together after two cell-searches in the one day and we spent the night sleeping on the heating pipes. But again we could see where that kind of protest would take us and we were still only on remand.

Then we wanted to batter – if not worse – one of the screws but were again advised against it. But we did have the consolation of seeing the state the screws would get into after a two-week shift on the wing. They’d be utterly shattered and couldn’t wait to get away form us. We were hard work all right.

My role in jail was of entertainer. I’d sing every night out the window in response to the endless requests of the men in the surrounding blocks. The acoustics of the exercise yard in A-Wing were a model for aspiring talent like mine but the next day the screws would come to the door and put me on report for ‘disturbing the neighbours’. They said there were complaints! The ingratitude of it all.

Myself and Ella were always a bit nuts so we can’t blame long-term imprisonment. We decided that for the last day of the trial at the Old Bailey we’d try and dress like Tricolours. We literally wore green, white and gold. Luckily nobody noticed! Boreham was the name of the judge handing out the life sentences and half the time he was asleep during the proceedings. He was so old he should have been at home praying for a happy death!

In the middle of the constant bombardment with strip-searches, cell-searches and ongoing harassment we found a friend, a woman called Nina Hutchinson, who has sadly died since. Nina visited us regularly and was the instigator of a strong campaign around prison conditions in Brixton and later in Durham.

• Ella and Martina at the 2008 Le Chéile

As for Durham! It took me a whole week to realise I wasn’t in a hospital. In fact it took me a week to even talk really. But that wasn’t too bad. There was a woman who’d been there for years and she never spoke at all. Another woman used to burn herself with fags. There were so many unwell women in H-Wing who, instead of being sent to jail, should have been sent for psychiatric care.

One of the first people we met in Durham was Judith Ward [convicted of bombing a British Army coach on the M62 in England].

She bounced up to us and asked us if we’d like to come to her cell for a drink. A drink! Ella and I exchanged wide-eyed glances. Hooch, we figured. Could it really be? We moved swiftly to Judith’s cell. In fact, I think we got there before her. She produced a flask, three tea bags and a jar of coffee. Not quite the same thing as hooch but she did have some traditional Irish music that the Gillespie sisters had left with her on their release.

Another person we met the first day in Durham was a Scottish woman who greeted us with “I’m a prostitute, a lesbian and I’m in for murder – and how are you?” We became friends and, thankfully, she left it until the day before we left H-Wing for good to tell me she fancied me! I was a happily married woman.

Both Ella and I had jail weddings. Ella’s was a nice day but my wedding in 1989 [to IRA POW Paul Kavanagh] was more like an obstacle course. By the time I’d been driven a mile a minute on the four-hour journey to Full Sutton Jail, near York, vomiting all the way and given a couple of brief hours to get the business done and rushed back to H-Wing again, I was totally bewildered and upset. Ella jumped to the wrong conclusion at the sight of me. “Don’t worry, all’s not lost – we’ll get you a divorce!” That really did it and I didn’t sleep a wink that night.

We didn’t just celebrate weddings. We made a big thing of Christmases and birthdays. In fact, I remember Ella’s first mid-life crisis – she was 30 and was utterly miserable. On such occasions we’d exchange gifts and get spoilt by our families when they’d come on visits. If one of us got something, the other one did too. The Andersons to this day will never forget traipsing around the streets looking for prawns for Ella. Prawns! You can imagine the searching the screws did on the big basin of prawns that was enough to feed an army.

My mother, Betty, was the rock in our household right throughout my sentence. I will always love her.

But it wasn’t all partying and we spent the first six months of our time in Durham on ‘lock-up’, meaning everything, including the mattress, would be taken out of the cell and you saw nobody except the screw who came to let you ‘slop out’. We didn’t even get to see each other.

The governor let us know that he had been governor of Wakefield when Frank Stagg died and he’d happily send us home in boxes.

If you needed a lesson on the inhumanity and brutality at the core of imperialism you only had to look at the way prisoners were treated – even the sick and vulnerable ones we saw in Durham. We wanted to change it all, change the world we were living in, and in a way we did just that.

By the time we’d been transferred from H-Wing, the jail had been refurbished to a relatively habitable state with toilets and hand-basins in each cell. After threatening to wreck these pristine abodes if we weren’t allowed to inhabit the ones on the upper floors, they agreed to let us onto the top landing. So, for the first time in about eight years, we had a view of normal daylight from our cells. I remember waking up the first morning and banging on the door, shouting to the women to look out the window. It was a great big beautiful orange ball – the sun was rising. It was magic!

Le Chéile Munster Honouree : Ella O’Dwyer

First published: 28 February 2008

No ordinary woman

ELLA O’DWYER, from Gortnaskehy, Roscrea, County Tipperary, is the 2008 Le Chéile honouree for Munster.

Ella served over 13 years of a life sentence, nine of which were spent in English jails and the remainder in Maghaberry Prison. Sentenced in 1986 after being arrested in Glasgow the previous year with Martina Anderson, Gerry ‘Blute’ McDonnell, Peter Sherry and Pat Magee (‘The Brighton Bomber’), she was released in 1998 under the Good Friday Agreement. Having spent regular periods of solitary confinement in Durham Prison, Ella and her republican comrade, Martina Anderson, forced the British Home Office to acknowledge the inhumane conditions in prisoners where held in one of England’s most notorious prisons - H-Wing, Durham. PHILIP LACKEN looks back at her life so far.

• 2008 Le Chéile hounourees - Brian Keenan, Joe Desmond (accepting the award on behalf of Kathleen Glavey), Ella O’Dwyer, Áine Ní Gabhann and Jim Slaven

HAVING graduated from University College Dublin in 1982 with an honours degree in English, Linguistics and Philosophy, Ella became politically active during the first H-Block hunger strike of 1980 and cut short a back-packing trip to India when she read of the renewal of the hunger strike in 1981.

“I remember on the journey reading in a German newspaper the headline, ‘Right Honourable Member of Violence,’ and I knew Bobby Sands had won his seat.”

But her interest in republicanism was spawned, not in Tipperary or UCD, but as a voluntary worker in a German children’s playgroup.

“The people I worked with in my late teens used to think that I was English, purely because of the British presence in Ireland. I argued that we’d won the 26 Counties back but it got me thinking – about what it was to be Irish. It had never dawned on me before then that I could be seen as anything but Irish. Sometimes you have to leave your environment in order to define what that environment actually is and what it means.”

With a razor-sharp intellect and an engaging passion for history, Ella is unassuming regarding her life-long struggle that has brought her the Le Chéile honour. “I’m proud for my family who suffered a lotwhile making repeated trips to English jails.”

As in so many Southern homes, republicanism was a silent given. Ella’s father, Billy, died just a fortnight ago and is survived by Ella’s mother, Nora, one sister (Marian) and four brothers (Darby, Philip, Liam, and Patrick). Another brother, Martin, died in May 1975.

“After I came out of prison I discovered my families’ empathy with republicanism of the late 1920s when my grandfather, Martin O’Dwyer, sheltered Volunteers like Tracey and Breen. I remember also that during the Hunger Strike my mother marched beside me on occasions and insisted on putting money into a collection box at the GPO.”

• Mary Lou McDonald, Gerry Adams, Ella and Eddie Butler

Her incarceration began when she was arrested in Scotland for conspiracy to cause explosions. “My parents didn’t know to what extent I was involved and didn’t believe the charges would stick.

“Conspiracy is a law that if you’re charged with it, it sticks. That is what it is designed for.”

And stick it did. They served 13 months on remand in Brixton Prison in south London.

“The ma and da would write every week. I remember a witty poem the da sent about the ‘free food and free electricity’ that myself and Martina Anderson were getting.

“My father was in poor health while I was in jail in England. He took a trip over to visit me – his first trip out of his country. He was stunned at the length of the queues in the supermarkets in Brixton, saying he felt like a child locked out of a sweet shop. He didn’t notice that there was hardly any white people living there.”

Ella was given a life sentence at the age of 26 along with her comrade, Martina Anderson, and both were eventually sent to Durham Prison.

“I had my immediate family and I also had my republican family. The structure that I operated in was like that of a family. So in that sense we didn’t let prison get to us. To ordinary prisoners in Durham there was a sense of utter hopelessness and despair. Because we were republicans – Martina Anderson, Martina Shanahan and myself – we set about changing prison conditions.”

Ella says the medical staff there almost systematically promoted hysterectomies to be carried out on the unfortunate and usually disturbed inmates in Durham.

“It was relatively easy for the few political prisoners in H-Wing, Durham, because we knew we could stick it out to the end. Many prisoners were in poor physical condition and the doctor would stand there and permit repeated periods of solitary confinement, regardless of how physically fit the prisoner might be. This went on all of the time. H-Wing was closed down in recent years.”

• Ella and Patrick Hackett

The determination that saw her outlast the daily horrors of Durham still shine through.

“All republicans, regardless of their current stance on the peace process or whatever, together, we’ve overcome these many obstacles.

“In the end, the Brits had to choose between reforming Durham prison and their illegal, degrading treatment of its prisoners, or close it down altogether. Those doctors must be turning in their graves to know that the inmates there have Irish republicans to thank for giving prisoners back some of their dignity.”

Ella is a staff writer here at An Phoblacht and, having already written a highly political book entitled The Rising of the Moon, she feels that she may well write another.

Her primary concern, though, is for the republican family and its unity of purpose.

“I dislike this term ‘dissident’ republican. We should not lose sight of the fact that it’s the British occupation of our country that is the issue. The British have always divided and ruled with a ruthless efficiency. The imperialists will continue to do what imperialists do. The struggle did not start in 1916 – it started the day the English claimed dominion over us and it will finish the day they leave. That may not even be in my lifetime, but I believe it will.

“Our generation of republicans has achieved so much. But the way I see it, we don’t need the war anymore; it has taken us as far as it can. There is no point in another generation of Ireland’s youth spending their lives in prison, dying in the streets or on hunger strike in some wretched hospital wing. We did that so that the next generation wouldn’t have to.

“The recent death of Brendan Hughes is mourned by all of us. We mourn one of our bravest and most intelligent Volunteers and I’m proud to call him comrade. If the republican family can summon up our united strength, our day will certainly come, and sooner rather than later.”

• Ella interviewing Bobby Storey for An Phoblacht, December 2008

Ella O'Dwyer funeral arrangements

Follow us on Facebook

An Phoblacht on Twitter

Uncomfortable Conversations

An initiative for dialogue

for reconciliation

— — — — — — —

Contributions from key figures in the churches, academia and wider civic society as well as senior republican figures