29 February 2024 Edition

Breaking the chains of silence

Shedding light on the plight of women political prisoners

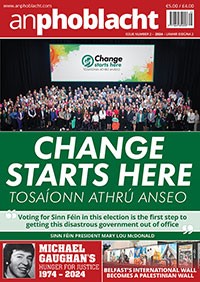

• Kurdish Free Women’s Movement (TJA) Conference attendees

At the heart of a global struggle for women’s rights and justice, a Kurdish Free Women’s Movement (TJA) Conference held in the Kurdish city of Amed, titled ‘Breaking the Chains of Silence’, emerged as a beacon, shedding light on the plight of women political prisoners in jails worldwide.

The conference, a platform for solidarity and advocacy, brought together remarkable voices and I was honoured to represent my Republican female comrades who have experienced incarceration.

Given the patriarchal societies we women were born into, we were not seen to have a role in a struggle that was the sole terrain of men.

Defying societal norms meant that we women, whom society placed in the home cooking, cleaning, and having babies, were punished more severely for having the audacity to be warriors, for standing up and fighting back. And the prison regimes we entered adopted a more punitive approach towards republican women.

Among the attendees were Kurdish women, former political prisoners, two of whom had served 30 years each in jail, alongside representatives from Basque, Palestinian, and Iranian communities. The narratives of women from all over the world was inspiring.

Also discussed were a demand for freedom for Abdullah Öcalan, who has been imprisoned for 25 years and is kept under isolation in İmralı, as well as the prospects for a solution to the Kurdish question, and the hunger strike launched by Iranian political prisoners on 27 November 2023.

The conference aimed to expose practices designed to break the will of the women political prisoners with details of sexual violence recounted – rape, electrocution, strip searching and solidarity confinement that persists in the harrowing experiences of women detained for their political beliefs.

The broad range of women who outlined their experiences underscored the interconnectedness of struggles, weaving together the narratives of women from various regions facing political persecution.

I brought a perspective that resonated with the challenges of navigating political landscapes where women’s voices are often marginalised. I emphasised the need for global solidarity, for an international women network to confront the systemic injustices faced by women political prisoners in custody which allowed such abuses to persist unchecked.

• Ella O’Dwyer and Martina

My comrade Ella O’Dwyer and I were held in Brixton, a men’s jail with 600 men and only us two women. We were mainly locked up for 23 hours a day. We were legally entitled to one hour’s exercise, and we needed to get out of the cells.

We walked daily around an enclosed area bordered by three male prison wings. We adapted by focusing solely on each other, tuning out the disturbing sexual remarks hurled our way. Some of the male inmates resorted to appalling behaviour, shouting explicit obscenities, and engaging in indecent acts of sexual exposure from their cell windows.

The Kurdish women in attendance, some having endured 30 years of imprisonment, provided firsthand accounts of the egregious conditions within jails. Their stories wove a tapestry of resilience and resistance against oppressive regimes.

These women had become symbols of endurance, inspiring others to break their silence and challenge the injustices perpetuated by authoritarian regimes.

For many women political prisoners serving long years in jail, we pass our childbearing age, which is one of the many unspoken truths which stands in stark contrast to men. A male prisoner, political or otherwise, could be released in his 60s and older - and still father a child. However, that is not the case for us women.

I recounted my personal experience. Ella and I used to say that the gynaecologist in Durham Prison was on commission because of the number of women prisoners he performed hysterectomies on was alarming. He told me I needed a hysterectomy for dysmenorrhea. I refused. He took me to an outside hospital to have polyps removed from my womb. I was supposed to be held overnight after general anaesthetic surgery.

Instead, I was dragged out of theatre after 30 minutes, unconscious and only momentarily semi-conscious and bundled into the back of a prison van with a hospital gown lying open revealing my naked body. With blood running down my legs, I was carried back into the jail semi-conscious.

I haemorrhaged during the night and refused to go back to that hospital after the earlier ordeal. They brought in medics. Apparently ‘Dr Death’ as Ella and I called the gynaecologist ‘accidentally’, I say on purpose, damaged my uterus. I was told it was no big deal because by the time I would be released from prison, I would be well passed my childbearing years.

The conference amplified the voices of Basque, Palestinian, Syrian, and Iranian women who shared similar experiences of abuse and degradation.

The threat of sexual violence became a stark reminder of the universal challenges faced by women political prisoners. One harrowing tale that emerged involved a woman political prisoner who was raped while in custody. Shockingly, her husband left her, branding her as “unclean”.

This heart-wrenching revelation highlighted not only the physical and emotional toll of sexual abuse, but also the societal stigma that further victimises survivors.

The woman’s story underscored the urgent need for systemic change and support mechanisms to protect survivors of sexual violence, both within and outside the confines of prison walls.

• Martina with former Kurdish and Palestinian political prisoners

The conference concluded with a resounding call for solidarity among women worldwide. It was recognized that breaking the chains of silence required a collective effort to challenge the systemic structures that perpetuate the abuse of women political prisoners.

The stories shared at the conference became a catalyst for change, sparking renewed energy and determination to advocate for the rights and dignity of women facing political persecution across the globe.

Breaking the chains of silence was not just an event. It marked the beginning of a united front against the injustices that women endure in their pursuit of human rights, social justice, and equality.

Martina Anderson is the Sinn Féin representative in Europe