4 July 2016 Edition

Trial and execution of Roger Casement

Remembering the Past – Aftermath of the Easter Rising

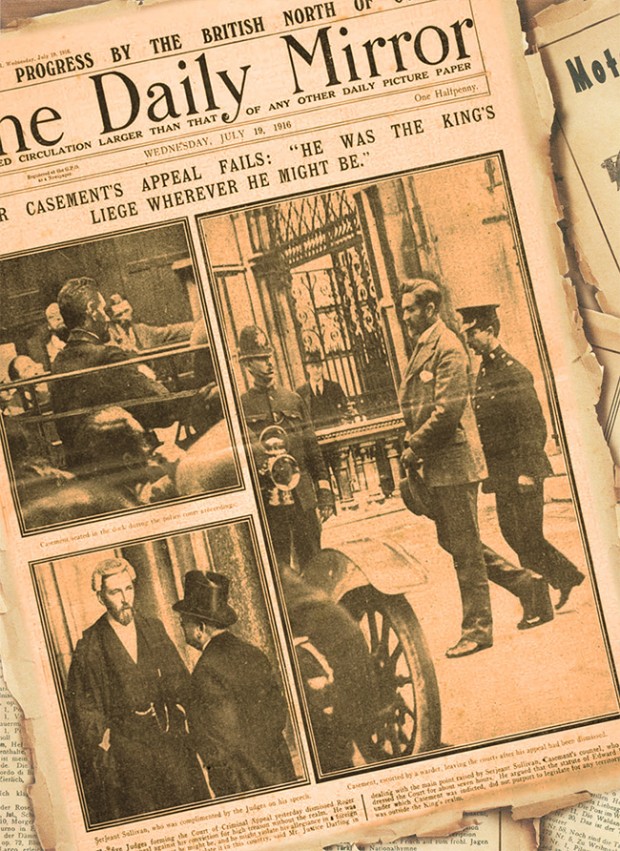

• Roger Casement's trial garnered a huge amount of media attention

"I am proud to be a rebel and shall cling to my ‘rebellion’ with the last drop of my blood" – Roger Casement

FOLLOWING the executions of James Connolly and Seán Mac Diarmada on 12 May 1916 in Dublin, the attention of the Irish people shifted to England, where Roger Casement was being held in the Tower of London, for centuries the traditional place of detention – and often torture and execution – for alleged traitors to the English crown.

Casement was brought before Bow Street Magistrates Court on 15 May. He had landed at Banna Strand in Kerry on Good Friday 21 April. The Irish Volunteers’ rendezvous with the German arms ship The Aud had not happened and she was intercepted by the British, then scuttled by her captain off Cork. Casement had been dropped at Banna Strand from a small craft after disembarking from the German submarine U19. There were no Volunteers to meet him and he was arrested and taken to Tralee and then on to Dublin. In Arbour Hill Prison he was treated roughly and strip-searched before being brought to London.

This was a prize capture for the British government. Casement was well-known internationally. He had been in Germany recruiting for his proposed Irish Brigade, to be made up of Irishmen who had been serving in the British Army and captured as prisoners of war. This venture was not a success but it deepened the hatred of the British Establishment for the man they regarded as a turncoat.

Eleven years earlier, in 1905, Casement had received his first honour from the British monarch for his humanitarian work in Africa. With the crusading journalist E. D. Morel, he exposed the horrendous, genocidal regime of King Leopold of Belgium in the Congo where millions of people were worked to death, mutilated, tortured and murdered as rubber was harvested from the rain forests. In 1910 he exposed similar atrocities in the Putamayo region in South America and received a knighthood the following year.

While Casement worked for the British Foreign Office he became an ever more convinced Irish nationalist and opponent of Empire. He joined Sinn Féin and Conradh na Gaeilge and was a founder member of the Irish Volunteers in 1913, helping to draw up their manifesto. With his County Antrim Protestant family background, he appealed to Ulster Protestants to join with their compatriots in support of Irish unity and self-government and against partition. He travelled to the USA and campaigned against recruitment to the British Army on the outbreak of the First World War.

Casement’s trial opened at the Old Bailey in London on 26 June 1916. It lasted only four days.

The prosecutor was F. E. Smith, the Attorney General of England. Smith was a high-flying Tory MP who had been to the fore in using the Home Rule crisis to threaten violence against the Liberal government, stirring up unionist sectarianism. He appeared on horseback at one of Edward Carson’s rallies and earned the nickname ‘The Galloper’. Smith went on to become Lord Chancellor.

• Edward Carson and F. E. Smith inspect members of the Ulster Volunteers

Casement’s speech from the dock ranks with Robert Emmet’s as one of the supreme expressions of Irish freedom by a prisoner in the face of execution. Found guilty by the jury on 29 June 1916, Casement rose to make a speech that he had prepared carefully. He challenged the right of the crown to try him under a mediaeval treason law and said the jury were not his peers as they were not Irishmen. Bearing in mind that Smith and his fellow Tories were now in the War Cabinet with the Liberals (having, in Opposition, threatened civil war a couple of years previously) Casement said:

“While one English party was responsible for preaching a doctrine of hatred designed to bring about civil war in Ireland, the other, and that the party in power, took no active steps to restrain a propaganda that found its advocates in the Army, the Navy, and Privy Council – the Houses of Parliament and in the state church.”

He slammed the hypocrisy of war propaganda and recruiting:

“We are told that if Irishmen go by the thousand to die, not for Ireland but for Flanders, for Belgium, for a patch of sand on the deserts of Mesopotamia, or a rocky trench on the heights of Gallipoli, they are winning self-government for Ireland. But if they dare to lay down their lives on their native soil, if they dare to dream even that freedom can be won only at home by men resolved to fight for it there, then they are traitors to their country, and their dream and their deaths are phases of a dishonourable fantasy.”

• Robert Monteith with Roger Casement and Daniel Bailey on a German U-boat on their way to Ireland, April 1916

Casement concluded with defiance:

“If it be treason to fight against such an unnatural fate as this, then I am proud to be a rebel and shall cling to my ‘rebellion’ with the last drop of my blood. If there be no right of rebellion against the state of things that no savage tribe would endure without resistance, then I am sure that it is better for men to fight and die without right than to live in such a state of right as this.

“Where all your rights have become only an accumulated wrong, where men must beg with bated breath for leave to subsist in their own land, to think their own thoughts, to sing their own songs, to gather the fruits of their own labours and, even while they beg, to see things inexorably withdrawn from them, then surely it is a braver, a saner and truer thing to be a rebel, in act and in deed, against such circumstances as these than to tamely accept it as the natural lot of men.”

Roger Casement was hanged in Pentonville Prison, London, on 3 August 1916.